The Inception of Dayton Police Crisis Intervention Teams (1967-1980)

In the 1960s, societal attitudes regarding governmental authority were rapidly changing and police officers were representative of that authority. Challenges to police practices led to court-mandated reforms affecting the way by which law enforcement could operate. One of the Dayton police force’s earliest tactical team leaders, Sgt. Michael Brannen, recalled that police departments believed, but were unwilling to say, that citizens had totally lost respect for “the regular police officer on the streets”. Changes in the law were controversial but advanced the cause of the civil rights movement in all its realms; consequently, the “heavy-handed tactics of the ‘old school’ were not as acceptable” as they had been in the past. Sgt. Brannen noted that it took some “progressive thinking” on the part of police commanders to establish contingency plans for dealing with disruptive activities or crisis situations and, to do so, having well-trained specialized teams to handle crises were essential.

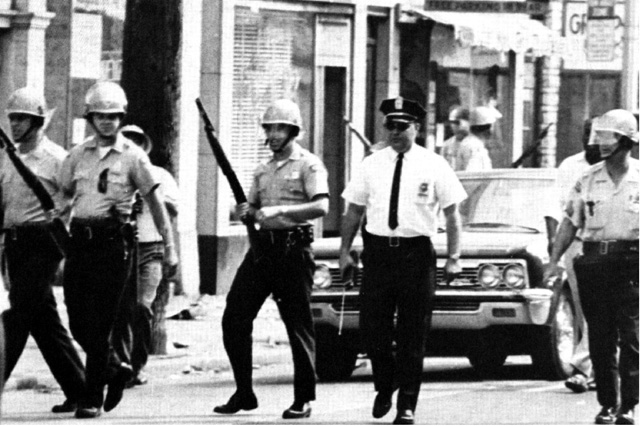

Officers led by Capt. Paul Stewart maintain order during Dayton riots.

What was alarming to the police establishment were highly publicized crisis incidents that were occurring on a national level (prominent examples were the outbreak of race riots in large cities around the country and the August 1, 1966 Texas Tower Massacre - a sniper shooting – on the campus of the University of Texas in Austin) followed by local experiences that required authorities to call in the Ohio National Guard. There were three days of rioting in west Dayton erupting on September 1, 1966 as well as rioting surrounding a speech in Dayton by black activist H. Rap Brown the following year. On August 1, 1967, Brown was arrested in Dayton for “advocating criminal syndicalism”. In the aftermath of these atypical but more frequently occurring events, the Dayton Police Department (DPD) took steps to form its first specialized crisis intervention unit.

In 1967, the Heavy Weapons Team (HWT) was created and its first commander was Lt. Lyle Grossnickle. The team was comprised of members of the Academy Staff, primarily the firearms range and self-defense instructors: Sgt. Michael Brannen and Patrolmen James Miller, Robert Norris, Fred Wade, Billy Crumbley and eventually Dale Tullis. When Lt. Grossnickle was reassigned to the new Team Policing 5th District in 1970, Sgt. Brannen took over the HWT.

According to Sgt. Brannen, the HWT was to be a “cadre of officers” that purposely spent training time fully familiarizing themselves with all the weapons in the Dayton police arsenal. Those officers did a fair amount of training during their off-duty time, because they were highly dedicated to the concept (“and possibly gunslingers at heart”) and also because scheduling specialized training was difficult at that time.

The unique element of this and other teams to follow was that membership was not a full-time permanent assignment. Officers were selected based on performance and willingness to make themselves available for both tour-of-duty and after-hour emergency callouts. It was auxiliary duty. In many cases, the officers on specialized teams were those that were dedicated to advance the cause of the team in additional training and equipment maintenance during uncompensated off-duty time.

There was reassurance for the public and command knowing that DPD had a Heavy Weapons Team; however, according to Sgt. Brannen, the HWT was rarely deployed in a tactical capacity in the early years (once for a Presidential visit to Dayton and another time for a publicized pot-smoking rock concert at Eastwood Park in 1977). Its primary role was in providing expert guidance to patrolmen that came across situations needing special handling. Nevertheless, the advanced weapons training did prepare the HWT to respond to crises that might arise.

After two years of civil unrest on the streets of the city, a potential sniper attack was a concern of the DPD. A select, trained “anti-sniper squad” (unofficial title) was established as part of the HWT. The community turmoil of the 1960s continued into the 1970s. Problems were emerging at high schools and in neighborhoods with some youngsters adopting the ideology of the Black Panther Party, the Black Guard and Chains of Rap Brown and, conversely, the pushback from other youths. On a national level, repeated episodes of violence - particularly aimed at police - were in the news and on law enforcements radar.

Officers confronting gunfire was an expectation of the profession but a new and far more serious form of deadly aggression was surfacing among anarchist groups. Around the country, the police and others were being targeted with bombings. As examples, the Weather Underground Organization (the Weathermen) detonated dynamite explosives in a NYPD police headquarters. An attempt was made by the Symbionese Liberation Army (SLA) to explode a bomb under a LAPD patrol car.

In 1973, a second specialized crisis police team emerged to address the potential threat of explosives. The Dayton police Bomb Squad was created. Detectives William Fricker and Claude 'Bud' Spitler, Dayton Police arson investigators, were the first bomb technicians. They were extensively trained at the Hazardous Devices School (HDS) at Redstone Arsenal in Huntsville, Alabama. This partnership of bomb experts lasted until both men were hurt in a building collapse while investigating an arson fire.

As Dayton headed into the mid-1970s, controversial nation-wide efforts to racially integrate schools were court bound. A 1971 judicial ruling in Charlotte, North Carolina set in motion the contentious matter of ‘school busing’ but in 1975 a federal judge in Dayton more broadly interpreted how to accomplish school desegregation. As opposed to the Charlotte standard of limited busing to areas determined to be racially imbalanced, Dayton’s federal district court ordered busing for the entire Dayton public school system. This ruling had national impact. Community debate and tensions rose as the implementation of the school busing plan neared. Dayton’s “Anti-sniper Squad” was at first assigned to overtime details but this then led to the formation of a School Desegregation Task Force to safeguard the schools until authorities were certain there would be no resultant violence.

As clear as it was that weapons and explosives expertise was valuable to the DPD, it was apparent to team members that knowledge alone had limitations. In the early years, the DPD invested in training for its HWT and Bomb Squad members but it did not have the financial resources to further invest in necessary equipment. What the DPD had in weapons and other modest gear were maintained in the Emergency Equipment Room, located in the Dispatch Center at the Safety Building. In the event of a crisis call out, one or more team members would first have to stop at this “ready room” as it was called to pick up specialized equipment that the DPD had available (i.e. weapons, bullhorn, ballistic vests, etc.). As an example, and in fact, HWT members halfheartedly utilized the DPD’s only four ballistic vests located in the ‘ready room’ because they were impractically heavy and limited an officer's mobility:

Unlike the light-weight Kevlar bullet-proof vests issued to today’s patrol officers, the four ballistic vests obtained by DPD in the 1960s were heavy, had solid plates of a fiberglass composite and a ceramic frontal facing covered in Naugahide. They were actually U.S. military body armor marketed to police departments as the War in Vietnam was winding down. These vests had bona fide stopping capability but could only take the impact of one shot. If hit by a 30-06 shotgun or rifle round, the plate would break, leaving an officer vulnerable to subsequent hits. DPD tactical officers knew this was the case and did not expect the vest would protect fellow officers if struck by multiple shots. On the other hand, this vest was an early way to protect members of the Bomb Squad from an initial impact blow of an explosive. This remained the primary explosive shield for members of the Bomb Squad until 1991.

Even though the HWT and the Bomb Squad were two separate specialized units, by 1977 both were placed under the direct supervision of Lt. Billy Faulkner, the newly appointed HWT commander. In the spring after the School Desegregation Task Force, the HWT was renamed the Tactical Response Team (TRT), the forerunner of today’s SWAT Team. At the time, the Dayton Police Department was opposed to naming its reconstituted team after the popular 1975-76 television program, S.W.A.T.

The Tactical Response Team before its members had uniforms.

Lt. Faulkner began replacing members of the older unit. Unlike today, the original TRT and Bomb Squad did not have members outfitted in identifiable team uniforms. Generally, the officers responded to crisis scenes in civilian attire. Also, in the early years, the specialized units were initially left to their own devises to obtain better equipment and improve upon it. Even into the 1980s, for an applicant to be chosen for the TRT, he had to own a truck in order to pick up ‘ready room’ equipment.

DPD investment in the best available training was still being done and the members of the TRT were place under the teaching guidance of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). The TRT began to evolve into a unit whose actual utility corresponded with its name: a tactical team that responded to act on high-risk emergencies.

In 1978, a new and complimentary concept was also adopted by the Dayton Police Department: hostage negotiations. Although this concept was neither initially nor readily accepted by rank and file members of the Dayton Police Department or by many members of the TRT, it would become the glove-on-the-other-hand in crisis callouts. What started with one lieutenant would turn into a complete team by 1980: the Hostage Negotiation Team (HNT).

Changes for the TRT and Bomb Squad (1981-1992 in brief)

As the 1970s closed, Dayton’s three crisis intervention teams would capture the attention of the public and the news. As they developed in the 1980s continuing into the 1990s, these teams would gain recognition for exceptional levels of performance and serve as guiding influences for many other law enforcement agencies. Growth into the skills and appearance of today was gradual for these three teams.

After Detectives Spitler and Fricker were injured, a change in personnel on the Bomb Squad was necessary. Lt. Faulkner replaced these two detectives with members from the TRT: Sgt. Dennis Chaney, Off. Mark Lucas and Off. Dan Hall. These three officers served on both specialized units throughout the 1980s.

Tactical Response Team in 1st uniforms in mid-1980s.

By the mid-1980s, all three teams began to receive funding to procure uniforms, equipment and vehicles necessary to advance to greater levels performance. Sometimes the purchases were reluctantly accepted by team members. As an example, the TRT was the first team to issue its members specific team uniforms: dark blue pants and jackets. The team was not particularly proud of the uniforms, referring to them as “garbage man” or “Jiffy Lube” uniforms. That same attitude was true among members of the HNT when they first acquired blue “paramedic” uniforms a decade later in 1995. Despite dissatisfaction, uniforms made the teams identifiable to the public. By 1989, the DPD had established line-item equipment budgets for the TRT and HNT.

In June 1991, Lt. Faulkner retired. The TRT and Bomb Squad were initially placed under the guidance of Sgt. Chaney; however, within six months, the Bomb Squad and the TRT would come under separate command. Sgt. Chaney retained the Bomb Squad and Lt. Robert Chabali took charge of the TRT, renaming it the Special Weapons and Tactics Team (SWAT) in 1992. The members of the Bomb Squad were eventually outfitted in identifiable uniforms and the team was eventually renamed the Explosive Devices Unit (EDU).

SWAT, EDU and HNT experienced substantial team development from the early 1990s continuing into the 21st century. In large part it was attributed to the teams’ acquisition of armored and high-tech equipment/vehicles over the past two decades. The quality and array of equipment employed by the three teams is a story in itself as is the further evolvement of the teams. As it stands today, the teams’ have found balance between the highly-trained professional skills they initially achieved and their eventual acquisition of quality hardware and modern technology.

Return to "Dayton Hostage Negotiation Team" Home Page