Captain Amos Clark: Dayton Deputy Marshal and Policeman

The 1850-1890s lawman is an enigmatic figure in local history

--by retired Dayton Sgt. Steve Grismer

In the Wright Dunbar district, tribute is given to many prominent Daytonians with engraved inscriptions on the Walk of Fame. The Dayton Metropolitan Library is filled with accounts about the lives of the founders of Dayton, its principal government officials and industry leaders. Nearly every person who has had a noteworthy role in the development of the city has a written profile in resource publications… even if just a few passages memorialized for historical context. But look around the local research centers and no biographical sketch will be found on Amos Clark.

Amos Clark was a key member of the original Dayton police force established in 1873; however, the true measure of his law enforcement career remains a mystery as is his full story. In the years before and after 1873, Clark served as a deputy marshal and, multiple times, as “captain” of police. A chronicle of Amos Clark is not solely of him… it is also the story of early law enforcement in Dayton and the formation of a city of Dayton police force.Locally, Clark was in the midst of a profession in its developmental infancy.

Modern policing began in London, England in 1829. The concept of a single force of constables –enforcing local laws anywhere in the town and funded through enacted taxes – was an entirely new approach to crime fighting. Less than a decade later, this innovative means for maintaining societal order traveled overseas.

The first police departments in the United States formed over the course of 17 years on the east coast in three major cities: Boston (1838), then New York City (1844), and then Philadelphia (1855). The concept spread within three years to the country’s interior. In 1858 Cincinnati, the nation’s 6th largest city, established its police department. Dayton would follow suit shortly thereafter.

What is known about Amos Clark’s law enforcement career is that it began in 1850 (if not earlier) and continued through 1892. All indications are that his police career repeatedly started and stopped, rose and fell, throughout 42 or more years. He served at a time when political connections were paramount to receiving appointments and promotions or, when in disfavor of those in local power at any point in time, to being reassigned to lesser positions or completely separated from employment.

AMOS CLARK

No written account of Clark’s career has been found; the little that is known primarily comes from city government and employment data established in the Williams’ Directory of the City of Dayton, in Dayton Police Department annual reports, in the meetings’ ledger of the Board of the Metropolitan Police of Dayton, and in pieces found in other source documents including U.S. census data.

_______________________________________________

City Marshal–Ward Watchman method of policing

Amos Clark was born to Andrew and Mary Clark in Harrison Township, Ohio on January 27, 1827, according to one source. He met Henrietta “Harriet” Gilbert, who was a year his junior, born in Montgomery County on July 22, 1828. The two married on March 21, 1950 and had the first of three children in August. Clark was a lawman by then.

At age 23, Amos Clark was the city of Dayton’s “deputy marshal” in 1850 according to that year’s U.S. census and Odell's Dayton Directory and Business Adviser. The city marshal to whom he reported was S. L. Broadwell. The index entries offer no other constructive information on either man. It is a curiosity that Marshal Broadwell has the same surname as the city marshal in 1833, Ephraim Broadwell. Whether he is the same man, a familial relation or unrelated is not known. The year 1833, coincidentally, was when the city appointed its first “watchman”, Joseph L. Allen, to patrol a designated “square”.

No directories earlier than 1850 were found to determine if Clark had been a lawman in the 1840s; nor were proximate later directories found for the subsequent four years. The 1856 Williams’ Directory, and those that follow, begin to reveal the career of Amos Clark; he was the deputy to Marshal Samuel Richards. The actual date of Clark’s appointment (or election) is unknown but the term in office was two years. Local elections were always the first Monday in April and, so, the expiration of Marshal Richards’ term, and that of his deputy, was April 1857. The term would indicate that Clark served as a law enforcement official from April or May 1855.

The mid-1850s was a time when there was a breaking-and-entering crisis in Dayton. Ongoing research has shown, to a limited extent, the following circumstances:

Leading up to the crisis, in 1853 the city of Dayton had only one watchman per ward assisting the marshal, the deputy marshal with patrol and, presumably, assisting the two elected constables for other law enforcement duties. The six (6) existing wards were political subdivisions of the city.

The practical use of watchmen was a European tradition that remained unchanged from when it was instituted in colonial America in the 1600s. Watchmen were expected to be available at the call of the marshal, politicians and citizenry 24-hours per day, seven days per week, 365 days per year.

In 1854 and 1855, Dayton was victim to an “epidemic of burglaries”. [1] It was a crime spree much greater than a marshal, deputy and parochial ward watchman could handle. Citizens appealed to the City Council for action. On March 16, 1855 the City Council acted to address this specific outbreak of criminal activity.

According to one Dayton police record, the mayor was “ordered” by council to hire “one hundred” men to serve as law enforcement officers on a temporary basis. In another account, the mayor and marshal were “authorized… to appoint not more than 4 watchmen for each ward [24 total] to serve night and day at $2.00 for every 24 hours of service; but this was simply for emergencies.” [2] In neither account is there an explanation of whether an influx of appointments ever took place nor whether the burglary epidemicsubsided by either enforcement or time.

Undoubtedly, Amos Clark was one of the lawmen charged with ending the burglary crisis. He was the deputy marshal shortly after the 1855 council decree. He may well have been the deputy or at least a ward watchman in the immediate lead up to then, as the 1850 Odell index might suggest. The Williams’ Directoryentries unquestionably outline Clark’s law enforcement career during the last half of the 1850s into the 1860s, a period during which a force of Dayton “police” was initially being molded.

The change to a police force in Dayton was an evolutionary process. Not long after the first watchman was assigned to a designated square in 1833 under “the pay of individuals” [3] (i.e. privately paid), the marshal was authorized by city council to appoint “night-watchmen” for every ward. As previously noted, temporary ward watchmen were later authorized to be retained for the emergency of 1854-55. Whether the marshal acted on these authorizations or on the influences of city councilmen is not known at present.

The underpinnings in the ward-watch system (from which the term warden derives) is that those appointed as watchmen were residents of the ward, obligated as sentries for only their ward and recommended by and duty-bound to the elected ward official. There is no reason to believe the traditional practices or the expectations of ward-represented councilmen were different in Dayton than anywhere else in the country.

The permanent establishment of regular watchmen for every Dayton ward is still open to research although there is some indication that it may have begun in 1858. As to when ward watchmen came under the payroll of the municipality, as opposed to being “paid by individual subscriptions”, [4] is yet to be determined but by 1862 and thereafter every watchman is named by ward in the city government section of the Williams’ Directory and had established terms in office. One can gather from biennial citations of this nature that watchmen were in the employ of the city government.

Amos Clark was the deputy marshal for at least eight straight years from April 1855 (if not earlier) to April 1863. He served two terms under Marshal Samuel Richards into April 1859. He is listed in the directory as “Captain” in the deputy marshal capacity while serving with Marshal William Hannah for one term into April 1861. Again, Clark is listed as “Captain” [deputy marshal] while serving with his third consecutive marshal, Stacy B. Cain.

This record along with the Odell entry indicates that Amos Clark served at least 9 years in a deputy marshal’s position under four different men. There are two facets related to the directory data record of Clark that begs some speculation:

- The city marshal position was much like the county sheriff position in that it was an elective office.Amos Clark worked successively under three different marshals but never, himself, ascended to that high position. It could be he never wanted to run for office or he was simply not electable.

- In the directories for 1859-1863, he is listed under the city government police as “Captain Amos Clark”. This title coincides with efforts being made at the time to form an official police department in Dayton. The rank of “captain” would be tantamount to being the “deputy chief” in the chain of command to the marshal.

On September 3, 1858, Dayton’s city council officially declared that “the police department of the city shall consist of the marshal and 6 police officers.” [5] The mayor was authorized to establish rules for the officers and the marshal would act as the chief of police. In 1859 the composition of the Dayton police force slightly changed. It was at this time that the position of “captain” was added. One written account stated that the force was headed by the marshal and included seven (7) officers one of which [Amos Clark] was appointed to the rank of “captain”. This title corresponds with the entry for Clark in the Williams’ Directory.

The Civil War years – minimal development in local policing

In 1860 rebellion festered in the southern states and by 1861 state secessions changed the focus of cities from local crime to the looming national crisis. The regular police force remained eight (8) in size throughout the “War Between the States”. However, in furthering its effortsto organize a police department, in October 1861 a new lock-up facility was established when the Oregon engine house at the southeast corner of Sixth and Tecumseh Streets was turned into a police station house. Since 1856, the city’s first jail had been in the Deluge engine house on the east side of the 200 block of S. Main Street and, previous to then, a few cells in the basement of the county jail on west side S. Main Street at W. Sixth Street.

The term “policeman” was relatively new to the city in 1862… the officers were still labeled “watchman” under their individual occupations in the Williams’ Directory. In April 1863, the local directory showed that Issac Hale was elected marshal and, at the same time, Amos Clark departed from the force under conditions and for reason unknown. Clark was succeeded as police “captain” by Frederick S. Sage in 1863 and then Patrick O’Connell two years later. It could be that Clark fell into disfavor with the city council in 1863 or it could have been that he found better economic conditions with private employment.

The 1864-65 Williams’ Directory has Amos Clark laboring as a carpenter during the last years of the war. There is no indication that Clark enlisted as a soldier after he left the “police force” but there is evidence that he enlisted in measures to defend Dayton from the advance of Confederate forces when a military assault was most feared.

On June 15, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln appealed for 30,000 militia from Ohio to defend the north from General Robert E. Lee’s invading troops. Dayton sent its two volunteer militias south to Hamilton County but the rebel army’s defeat at Gettysburg brought both home. However, within a month, on July 13, the mayor of Dayton declared martial law when Confederate General John Hunt Morgan’s raiders made inroads from Kentucky into Indiana into Ohio. His troops headed north of Cincinnati and camped five miles south of Loveland.

The citizens of Dayton were panicked at the possibility they would be invaded. The city’s two militia companies headed south and“…all able-bodied men remaining at home were organized into companies and squads for defense. Pickets were thrown out on all the roads and the entire surrounding country thoroughly patrolled.” [6] Dayton’s six wards were divided into military districts. The 3rd District of the 5th Ward was placed under the command of Captain Amos Clark.

Rebel forces never invaded Dayton, Ohio. Morgan’s raiders turned northeast paralleling the Ohio River with the intention of crossing into West Virginia. Instead, Gen. Morgan and his troops were engaged by Union forces on July 26 in Salineville, Ohio and captured. The only feared threat to Dayton during the war had passed.

Post Civil War years – forward movement for local law enforcement

The Williams’ Directories between 1866 and 1870 list Clark’s occupation as “watchman” and “depot watchman”. These watchmen positions held by Clark were not city ward watchman positions; instead they would have been forms of private security. Nevertheless, Clark would resurface as a policeman in 1869, then in 1870 and, by 1871, his place in law enforcement would take to greater heights.

The post-Civil War years from 1865 to 1876 were a period of transformation for the police “profession” throughout this nation. States and cities were independently engaged in defining how best to implement this new method for maintaining law and order. The City of Dayton was no different. Hometown soldiers were also returning from war to Daytonto renew their lives. Many of these men were citizen volunteers and not professional soldiers. Some sought to adapt their acquired military skills to civilian life and the newly developing profession of police work suited their ambitions.

The war brought forth an improved railway system, industrialization and steady urban expansion. In 1866, Dayton had no actual police department but, as one of the nation’s more populous metropolises, it began to lay plans for one. Issac Hale continued to serve as marshal until 1867 and was succeeded by John Ryan who served until the marshal position forever ended in 1873.

At the start of the Civil War through the remainder of the decade, the City of Dayton was the 45th largest city in the United States, with an average population of 25,000 and swelling in size (it would remain a top 40s city for then next 100 years until 1970). On March 29, 1867, the Ohio legislature granted Dayton the right to organize a police department, as only “first-class” cities were entitled to do. Four members were appointed along with the mayor to serve on the “Dayton Metropolitan Police Commission”.

On April 22, 1867 police commissioners were charged with forming a department consisting of a “Captain and Acting Superintendent”, two sergeants and 20 officers to cover a city recently divided into 11 voting wards. The Commission made all police appointments, adjudicated all disciplinary matters, controlled the budget, and issued all rules and regulations (the first were adopted on April 25).

On May 13, 1867 Patrick O’Connell was officially appointed to serve as the head of the new Dayton Metropolitan Police Force. He carried the rank of “captain” which was now synonymous withbeing the “chief of police” in the chain of command. He reported to the police commission, not to a city marshal.

O’Connell had previously served as a colonel in the Union Army during the Civil War and then as the deputy marshal (“captain”) after the war. In May 1867 the police force was officially established and police appointments were conferred. Issac Hale became the “chief detective” and was allowed to retain the office of U.S. deputy marshal (however, shortly later he resigned from the force on August 26).

Noticeably not listed on the first police roster is one man with years of law enforcement experience and, arguably, the most in Dayton: Amos Clark. He also does not appear as a police officer in the 1868-69 Williams’ Directory.

The revocation of the Dayton Metropolitan Police Force

Politics being what it was in the 19th Century, on April 16, 1868 a new Ohio legislature repealed key provisions the act that allowed for the establishment of police departments in “cities of the second class”, those being only Dayton and Columbus in Ohio in 1868.

According to the meeting minutes of the Dayton Metropolitan Police Commission, on May 15 the commissioners “…therefore ordered… that the Metropolitan Police Force of this city is hereby discharged and relieved from duty from and after 7 o’clock p.m. ....” The city council was notified“to take charge of the Central Police House.” As a consequence, the council created a “Dayton City Police Board” but it officially returned the city to the old marshal form of policing under Marshal John Ryan and the ward-watch system. Dayton’s first manifestation of a municipal police department came to an abrupt end.

It would be five (5) years before a new, permanent metropolitan police force would be formed under sanction of Ohio law. In the meantime, the Dayton city council resumed protecting its citizenry with a marshal, captain and 22 “officers”, two for each of its 11 wards. Appointments were made annually by the mayor with the advice and consent of council.

Three months after the revocation of the City’s first police force, according to one account, Capt. O’Connell resigned as police superintendent on August 10, 1868; however, he may have served longer. The Board minutes name him in rank testifying in a disciplinary matter as late as January 9, 1869 and the 1870 A. Bailey Directory of the City of Dayton lists O’Connell’s occupation as “policeman”. Regardless of exactly when it happened, Capt. O’Connell did in fact leave and Marshal Ryan remained Dayton’s chief law enforcement official.

How the ‘council-marshal’ police force was structured and effectively operated from 1868 through 1870 is still open to research. The 1868-69 Williams Directory shows that only nine (9) men from the previous year’s 22-man roster were retained; 13 others were replaced. The supervision changed, too. The positions of sergeant were eliminated but the ranks of 1st and 2nd lieutenants were instituted. There is a record of state litigation that suggests that there was internal political turmoil in the new command and Amos Clark was a party to the conflict.

The record of the Police Board shows that on February 3, 1868, 2nd Sgt. Robert Evans was charged with numerous counts of neglect of duty as well as incompetence and conduct prejudicial to good order. He was found guilty and reduced in rank. John Kreidler was appointed 1st lieutenant and 1st Sgt. Shoemaker waselevated to the other position. However, under the reconstituted ‘council-marshal’ police force, the question of who had the authority to appoint lieutenants was at issue.

The state law had been amended so that the city marshal (not city council) was required to appoint lieutenants. Marshal Ryan appointed Amos Clark to 1st lieutenant on May 10, 1869 but he was not approved by city council (allegedly due to “defects” in the bond he posted). [7] Consequently, Clark did not assume the post. But Kreidler, who was not Marshal Ryan’s selection, continued “to discharge his duties” [8] and act in an official capacity believing that he was in fact the authorized police lieutenant.

In July 1869, John Kreidler was prosecuted locally for “usurping” the office of “first lieutenant of police for the city of Dayton.” [9] As a result, Kreidler was convicted and sentenced but he appealed the judgment of the court. This case worked its way to the Supreme Court of Ohio (66 Ohio L. 141). In the end, the Supreme Court determined that Kreidler had acted outside his authority but he did so in good faith. The court ruled that the conviction should be reversed. In the end, Lt. John Kreidler’s police career lasted less than a year and Amos Clark would resume his path in law enforcement a year later.

The 1870 A. Bailey Directory identifies Amos Clark as a “depot watchman”. In spite of this rudimentary job, on May 10, 1870,Amos Clark again emerged on the scene of local law enforcement and soon in a prominent way. The 1870 U.S. census lists Clark as a “policeman” and annual police reports show him to have been appointed as a “patrolman” on that date. Exactly one year later on May 10, 1871, the minutes of the Police Commission mentions Clark in a single entry but has himat a very different rank.

The journal minutes references “Capt. Clark” reporting to the Commission on a disciplinary matter. This title coincides with the 1872-73 Williams’ Directory which has listed under its city government offices “Capt. Amos Clark”, as well as John Ryan as the city marshal. The actual date of promotion is not known but, again, the term in office was still only two years. The expiration date for this term is listed in the directory as April 1873 indicating that Clark would have taken charge as “Captain” sometime from April to May 10, 1871, the date of the disciplinary hearing mentioned in the minutes.

The reintroduction of the Dayton Metropolitan Police Force

In early 1873, the General Assembly of Ohio passed a law allowing Dayton to place into effect what had previously been dissolved. What is now the Dayton Police Department was officially established May 19, 1873.

After two years, the term of Amos Clark had expired in 1873 and he was not asked to continue as “captain” in charge of the newly constituted and state-authorized police force. Instead, a former military captain in the Union Army during the Civil War, Thomas Steward, was sworn to lead the new metropolitan police force… although his service was short-lived. Steward resigned by August 9th under charges that he lost control of his command and for “bringing… discredit with said force.” [10] Failure to maintain order within the ranks was fatal to a career as a Dayton police captain.

On September 4, 1873, aformer Civil War Union Army general by the name of William Martin was the replacement appointment; his position retained the title “Captain and Acting Superintendent”. Capt.William Martin is recognized as the first head of the Dayton Police Department. Unlike Steward, Martin completed an authorized two-year term, the first man to do so.

The new Dayton police force numbered 35. It was comprised of two sergeants, three roundsmen (patrol supervisors), 26 patrolmen, and three turnkeys (jailers). Patrolmen walked their beats 12 or more hours per day, seven days per week and every day of the year. This was an average of three men per ward although the officers could and would enforce laws anywhere in the city (similar to London in 1829).

Although no longer captain of police, Amos Clark remained on the force and, on April 29, 1873, was appointed 2nd roundsman. This was a supervisory assignment in which he made the rounds ensuring the patrolmen were on actual foot patrol and not sleeping, drinking, gambling or visiting houses of ill fame for overly long periods of time.

This position placed Clark fifth in line in supervision behind the captain, two sergeants and the 1st roundsman. His previous experience held him in good stead, however. When the two sergeants were demoted and dismissed for charges of insubordination after the Steward incident, Clark was promoted to 1st sergeant on August 22.

Two years later on September 11, 1875 Capt. Martin retired with honor after his police career of two years (that same year Patrick O’Connell was named to command the newly established city workhouse jail). Capt. Martin was bestowed a “fine gold-headed cane” by the Dayton police force for his fine service. [11] In need of a new commander, the Board of Police Commissioners “elected” Amos Clark to fill the opening of Captain and Acting Superintendent. His responsibility was to act on the duties directed to him by the police commission for overseeing the police force.

Capt. Amos Clarkappears in the first known photograph of Dayton police officers. Taken in 1876, he is clearly one of the physically larger men… and front-standing in the police assembly. Capt. Clarkcontinued in his position for 5½ years, completing three consecutive “elected” periods in office. In terms of duration for a chief law enforcement official in the City of Dayton, this was unusual in its span.

Longevity in position does not necessarily translate as success. How well Clark’s command was received by the public and politicians is still open for research. It is known that several high profile murders occurred during Capt. Clark’s tenure.

On August 31, 1875, a very prominent citizen, Col. William Dawson, was stabbed to death outside a wedding reception on E. Fifth Street. The suspect was arrested by Dayton police, convicted and sentenced to death. A year later, the murderer was hanged under the oversight of Sheriff William Patton. This took place inside the county jail behind what is now the Old Court House.

On February 13, 1876, a Civil War veteran was beaten to death with a hammer outside a saloon near Warren Street. The suspect was arrested by Dayton police, convicted and sentenced to death. In anticipation that the day of reckoning would draw a large and potentially unruly crowd “from police headquarters came an official announcement that a detachment of police under Capt. Clark[was] assigned to duty both inside and outside the jail during the execution.” [12] As a pressing crowd amassed and spectators gathered to witness the deed the killer was dispatched for his crimein the summer of 1877, again from the end of a noose extended from the gallows inside the county jail. No disturbances occurred.

On January 17, 1880, Patrolman Lee Lynam was shot to death inside a saloon on his beat on E. Third Street. The suspect was arrested at the scene of the crime. Through a change in venue, the defendant was convicted of murder in Butler County and sentenced to 10 years in prison.

It is also known that at least one incident of disrespect by a subordinate to Capt. Clarkoccurred during his last term in office. It happened on July 23, 1880. Ptl. H. C. Decker posted on the public door of the central police station the following announcement:

“This evening at six and a half o’clock, come one come all we will open with prayer By Dog on it By Golly (meaning thereby Sergeant John F. Daniels). We will have the Baby Elephant perform his wonderful fete, that of Throwing both of his Ponderous feet on the table at once (meaning thereby the Captain and Acting Superintendent Amos Clark) the Duke of the Oregon Mr. Bucher will give one of his sleeping exhibits meaning thereby Roundsman Baker. By order of by God Capt Act Supt.”[sic] [13]

Charges were brought against Ptl. Decker for being disrespectful of his commanders. After the hearing, the patrolman resigned.

Whether it was high profile crimes or increased criminal activity or acts of defiance by subordinates, a change in command took place. One unsubstantiated police record has Patrick O’Connell returning to the police force on January 5, 1881, alluding to his completing Capt. Clark’s term in office. The Dayton Police Commission minutes have Clark resigning his command on April 16, 1881. He returned to patrol duties… but not for long. Clark was replaced by 1st Ward City Councilman George Butterworth, a man who had no previous experience in law enforcement with the Dayton police force but was on the council’s finance committee.

On May 1 Amos Clarkchose to resign from the police force after 10 years of continuous police service.

The appointment of a city councilman to head the police force was emblematic of practices during the formative years of both public safety services – police and fire. The fire department, similar to police, had been under city council management. This lasted for its first 15 years until 1880. Its first fire chief in 1864 was William Patton, the same William Patton who became the county sheriff and not too many years afterwards, the “police chief”. Politics played a significant role in appointments to the safety services. At least one account from 1880 indeed suggested that “it existed according to the caprice and schemes of the politicians, who either became councilmen, or who governed those who did. The consequence was progress and desired improvement [in the public safety services] was retarded….” [14]

Efforts were made to reform the system and eliminate politics from the control of the police force. Nevertheless, politics existed and undeniably influenced police leadership and, of course the reputation of the police force. And it wasn’t just politics. A few years into the mid-decade, the Dayton Police Commissioner Secretary, J. H. Ensign, embezzled over $2,500 from police funds and “absconded”. [15] The scandal brought fresh attention to control over the force but despite efforts at reform of law enforcement on by the Ohio General Assembly, major troubles persisted.

A Police Department “up to its eyebrows in sensations”

The 1881-83 Williams’ Directories show Amos Clark, for the two years after resignation, as having no employment and then a job as “clerk”. When City Councilman Butterworth completed his term as captain, he was replaced on May 1, 1883 by former Montgomery County Sheriff William Patton (1873-76). Capt. Patton’s appointment also saw the return to the force of Amos Clark, albeit at an entry-level post.

On July 2, 1883 Clark was appointed as a police turnkey… a central station house jailer. In 1888,Turnkey Clark appears in the second known photograph of an assembly of Dayton police officers. Taken in 1888, he is standing at the back of the men… but in front of a horse.

Amos Clark never again changed positions on the police force. He never rose in rank as he served under Capt. Patton and later Supt. William Shoemaker, a fellow Dayton police officer who rose in the rank to captain, and then Supt. Charles Freeman. Like Capt. Patton, Supt. Freeman was the former County Sheriff (1881-82) who was elected to be police “chief” (starting in 1887 the head of the police force was singularly titled “superintendent” of police). These leadership changes had signs of continued troubles.

Entering his second term in 1889, Supt. Shoemaker resigned from the police force for reasons unknown. Replaced by 2nd Ward City Councilman Albert Steinmetz, his command was as fleeting as Thomas Steward’s, lasting six months and ending four months before the term expired… vacated in January. Soon after the councilman’s departure in 1890, the City of Dayton had proud portrait photos taken of every one of its 70 police officers. Amos Clark is in the collage of those 1890 images… but on the bottom row.

In 1892, after nearly two years in office, Supt. Freeman was suspended and then forced out under allegations of serious misconduct (the pocketing of stolen jewelry). There was “rotten politics. The Department was up to its eyebrows in… sensations in the shape of shakeups, usually attended by… unsavory rumors…” [16] On May 16, 1892, Supt. Freeman was replaced by Thomas Farrell, a renowned Pinkerton detective from New Orleans.

Sometime in 1892, Amos Clark left the force forever after another 11 years of continuous service. The last entry in the Williams’ Directory for Clark as a policeman (“turnkey”) is in the 1891-1892 edition. The exact date and reason for his departure are not known. Poor health may well have been why he left because on December 18, 1892, Amos Clark died at age 65.

Amos Clark is buried at Old Greencastle Cemetery in Dayton’s Edgemont neighborhood. His wife of 42 years, Harriet, listed his occupation as “ex-police cop”. She is also buried in the family plot (year of death unknown) along with their three children. Alas, Amos and Harriet outlived all three: son Orlando H. (8-10-1850 to 12-8-1887, age 37), son Charles “Charley” H. (3-10-1852 to 4-13-1853, age 1) and daughter Cassa Ann (4-2-1855 to 4-13-1855, infancy).

The members of the police force moved on. Enamored by the Louisiana lawman from the day of his appointment in early 1892, the local press used the unofficial title “Chief Farrell” in its news articles extolling his investigative exploits. Although he would serve as the head of the Dayton Police Department for eight years – barely passing Amos Clark’s total years in command – Supt. Farrell like others before him was forced to resign. He left in disgrace on January 11, 1900 under allegations of immoral behavior with a teenage girl. The second in command, Capt. John Allaback, was place in charge on an interim basis of a police force now numbering 91 men (it would increase to 146 by the end of the decade).

Less than 10 years after Clark’s departure, and after a year-long search, Farrell’s replacement was John Whitaker. Appointed on March 1, 1901, Whitaker is recognized as the first to officially hold the title of “Chief of Police” (by municipal code in October 1902). Chief Whitaker’s command of the Division of Police marks the beginning of the modern era of law enforcement for the City of Dayton and an entrance into the 20th Century. It also marked the reform of the spoils system in local government. Rather than selection based on relationships, with the introduction of civil service standards, appointments required at least some minimum qualifications.

The legacy of early Dayton policing and Capt. Amos Clark

Had it not been for Chief Whitaker’s keen interest in photo imagery and his sense of historical legacy, Amos Clark might have been completely lost to time.

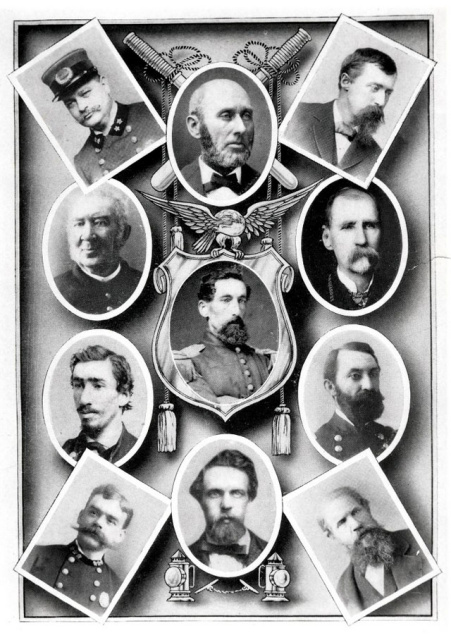

In 1907, following up on his 1902 police portrait book, Chief Whitaker had a Dayton police pictorial book published that comprehensively described the history of policing in the city “from the earliest times” to 1907. In that book, the Chief had the three photographs reprinted that depict Clark and other members of the police force. He also chose to have all past chiefs – be they “captain” or “superintendent”; celebrated, ordinary or ne’er-do-well – memorialized in a picture collage: O’Connell, Clark, Steward, Martin, Butterworth, Patton, Shoemaker, Steinmetz, Freeman and Farrell (as well as interim Supt. Allaback).

Dayton Police Superintedents

Center: Capt. Patrick O'Connell (1867-69); and Clockwise from upper left corner: Interim Supt. John Allaback (1900-01);

Capt. William Patton (1883-87); Councilman/Supt. Albert Steinmetz (1889) ; Capt. Thomas Steward (1873);

Supt. Charles Freeman (1890-92); Capt. William Martin (1873-75); Councilman/Capt. George Butterworth (1881-83);

Supt. Thomas Farrell (1989-1900); Supt. William Shoemaker (1887-89); and Capt. Amos Clark (1871-73; 1875-81).

The Dayton police background for these men is an appendage to other significant events in their careers. They had enough other life accomplishments that biographical profiles could be found on nearly all. O’Connell, Steward, Martin, and Patton were all ranking officers for the Union army, fighting in battles of the Civil War. Butterworth and Steinmetz were elected Dayton City Councilmen previous to their appointments and Patton and Freeman had earlier served as Montgomery County Sheriffs. Farrell was a nationally known detective.

They all have venerated histories with stories to tell but none of these men, with the exception of Shoemaker, served on the Dayton police force more than a fraction of the time as that of Amos Clark. Despite swings in his law enforcement career, Amos Clark accumulated an estimated 30 years of police service to the Dayton community. His career bridged the days of the ward watchman of 1850 to the threshold of modern law enforcement.

Amos Clarkwas a longtime deputy city marshal as well as Dayton’s captain of police… three times over… and yet he is the mystery figure! He may have been an exceptional law enforcement official… or he may have been a political pawn. Whatever the case, he is a man whose story needs to be uncovered and preserved. This account is a start.

_______________________________________________

Dayton Historian Curt Dalton and University of Dayton student Callum Morris provided significant research contributions for this account. Other resources and endnotes are as follows:

FamilySearch.org (online resource)

Spilt Blood – When murder walked the streets of Dayton by Curt Dalton

Record of the Board of Metropolitan Police of Dayton (1867-1882), Pages 58-60

History of the Police Department of Dayton, Ohio – From Earliest Times to October First 1907, Chief John Whitaker

Find a Grave – Old Greencastle Cemetery (online resource)

DaytonHistoryBooks.com (online resource)

[1] History of Dayton, Ohio 1889, Chapter 12, (1889) Page 208; and

History of the Dayton Police Department, Initial History of Dayton - Part Two (1907)

[2] Biography of Dayton, Part Three – Steam Power (1851-1909), Chapter III Politics; Evolution of Police Protection

[6] History of Dayton, Ohio 1889, Chapter 15, (1889) Page 310

[7] Reports of Cases argued and determined in the Supreme Court of Ohio, Volume 24 (1875), Page 23

[10] Record of the Board of Metropolitan Police of Dayton (1867-1882) Page 85

[11] Centennial Portrait and Biographical Record of the City of Dayton and of Montgomery County, Ohio Page 227

[12] This County’s Last Hanging, by Howard Burba (1930)

[13] Record of the Board of Metropolitan Police of Dayton (1867-1882) Pages 580-581

[14] Illustrated History of the Dayton Fire Department – The Paid Firemen, by J. E. Brelsford (1900)

[15] Ibid. 1 at Police History - First Patrol Wagon

[16] The Downfall of Chief Farrell by Howard Burba (1937)